Inverting the Human-to-Machine Interaction Contract

When Gutenberg’s printing press first blotted ink across parchment, humanity’s relationship with knowledge permanently changed. Ideas became accessible, and technological progress accelerated. Each epoch of innovation triggered societal shifts in line with Perezian cycles of disruption and realignment.

Inventions replaced physical labor, then enabled abstraction from hands to the mind. Today, machines encroach on knowledge work like law, finance, and research, professions propped up by prestige and credentialism. Not too long ago, I believed that modeling or memo-writing was a long-term differentiator. Perhaps I was naive, but no one expected those skills to decay in value as quickly as they did. I urge my investor peers to ask themselves: where’s our edge?

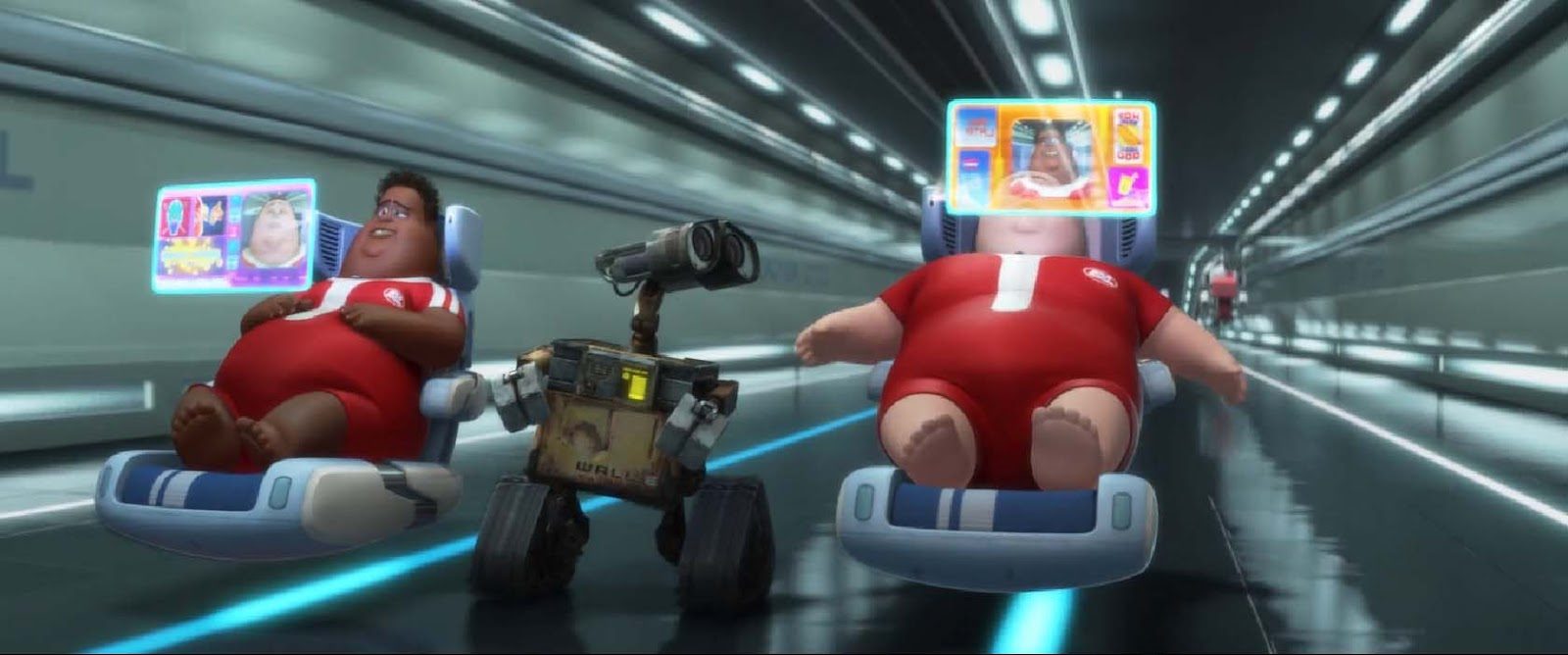

The compression from half-century to sub-decade technological cycles will surely impact our social and professional lives. Gian Segato wrote for Pirate Wires, arguing that agency will be the long-term differentiator in an AI-dominated regime. WALL-E-esque hedonism would be the most depressing mass-extinction event for humans, and so preserving our agency to use these new tools for our benefit is of utmost importance. This philosophical tension is explicit to the human condition… for now.

We must consider what happens when scaling laws enable machines to possess their own agency. What happens when there is an inversion of the human-to-machine interaction contract? Today, humans prompt machines to do something for us. We’ll soon reach a point where machines prompt humans to do something for them, or more optimistically, to do something for ourselves to better ourselves. When you crack open the hood, there are several inputs and complexities still required to make that a reality.

Victor Lazarte from Benchmark described this eloquently on a recent 20VC episode. He predicts an app that will nudge us: when to wake up, how to exercise, what to eat, how to work. I imagine a co-pilot for our day-to-day lives, allowing us to offload the cognitive burden of decisions. I expect this will be a wonderful world, though the bear case is frightening. Regardless, when we enter this post-inversion world, our roles as humans will change significantly.

Humans today still possess decision-making authority over machines. Dissolving that responsibility will be the final breakthrough required to invert the human-to-machine interaction contract. The next “unbreachable” domain will be social capital, and the new most valuable currency, goodwill. Navigating and managing relationships will be the most in-demand skill of the next decade as technical prowess atrophies alongside everything else.

Early-stage investors will grok this dynamic better than most others reading this, given that we engage in these behaviors every day. Venture is predicated on information arbitrage and speed. If an investor gains conviction on a founder before the rest of the market, they are rewarded with a lower entry price and thus greater convexity in their expected return. The most generous thing one can do is to introduce a blue-chip founder to an investor before the rest of the market.

Deal flow at the earliest stages often comes from other investors. In theory, high-quality information today should be rewarded with even higher-quality information tomorrow. However, the “coopetitive” interplay between investors means there’s some incentive misalignment. If one were to share a premium asset before they made an investment decision, they’d erode their alpha. But never sharing valuable information with peers results in being boxed out by the rest of the market. Reputation and social capital are everything.

My case up to this point is that these fundamental relationships will resist the progress of artificial intelligence for the foreseeable future. But as AI further abstracts knowledge work, I suspect even relationship management gets automated as everything quantifies.

Rex Woodbury at Daybreak recently published an overview of synthetic populations. This involves populations of AI agents with unique personas that simulate human behavior across use cases like local politics, marketing, and diseases. Agent-based modeling is already displacing political polls and focus groups.

I’m fascinated with distilling these simulations down to the micro – the individual person-to-person relationships we all possess. Reaching this point requires collecting immense amounts of data across individuals’ digital and physical worlds. Perhaps Mr. Ive will help us capture the full context of our lives. With perfect data about our entire beings, we may one day possess the information needed to make perfect decisions for every arbitrary situation. We could run millions of simulations to understand exactly how a decision will impact all of our relationships.

The Cluely team is provocative, but I can’t help but agree with the value in their long-term product vision, whether built by them or someone else. Having a miniature Nathan Fielder on our person – allowing us to rehearse any situation innumerable times – will prepare us and give us total contextual awareness of how others may react.

If we could capture every single interpersonal interaction and the results thereof, we may be able to quantify goodwill and form a marketplace of reciprocity. This already exists to some degree, but what if it permeates throughout life? What if we could call on favors in a quantifiable way? What if there were a way to predict the emergent behaviors of the complex systems that are our relationships? Is AI’s next “final boss” to make sense of this chaos and abstract away the fuzziness of relationships?

Inverting the human-to-machine interaction contract will be a fundamental shift in human identity and societal value structures. As we delegate decision-making entirely to AI, knowledge work’s relevance erodes further, placing interpersonal nuance and social capital at the forefront of human value. The complexity inherent in relationships remains our domain for now. As simulations grow more precise and contextual understanding deepens, even this frontier might succumb to automation. Our roles will soon transform from decision-makers to navigators of complex social systems. And once we surpass that, we’ll have to find something new to be best at, something more human altogether.