Meta-Risk in the Two-Party Venture System

Nate Silver has occupied a significant part of my life these past few weeks. Leading up to the election, I checked his Silver Bulletin forecasts every night alongside Polymarket (which he’s an advisor of). As a result, I figured now was as good a time as ever to read his new book, On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything.

In it he examines the River, a class of people who are inordinately predisposed to risk. People like gamblers, traders, and startup founders would be classified as inhabiting the River. For a chunk of the book, he opines on the world of venture capital and details the various ways in which they (we?) exhibit a high willingness to take risks by betting large amounts of capital on unproven companies.

And for the most part Nate’s right. Our industry started with Arthur Rock nudging The Traitorous Eight to rebel and start Fairchild Semiconductor. This spawned a web of the most important players in Silicon Valley – from Sequoia to Kleiner Perkins, from Intel to Apple. It was this risk to bet on a cadre of disgruntled scientists which planted the seed of maverick behavior throughout the technology industry. However, what is often overlooked in the story of Rock is what else he created. The 2 and 20 venture model was the result of him taking a 20% stake in Fairchild for his help in starting the business.

Since its birth in 1957, this 2 and 20 model has been the way venture capitalists make money. Now I won’t give a history lesson in all of the ways that venture capital has been attempted over the years as there are far better resources for that. But it’s striking that the economic model has remained largely unchanged for 66 years!

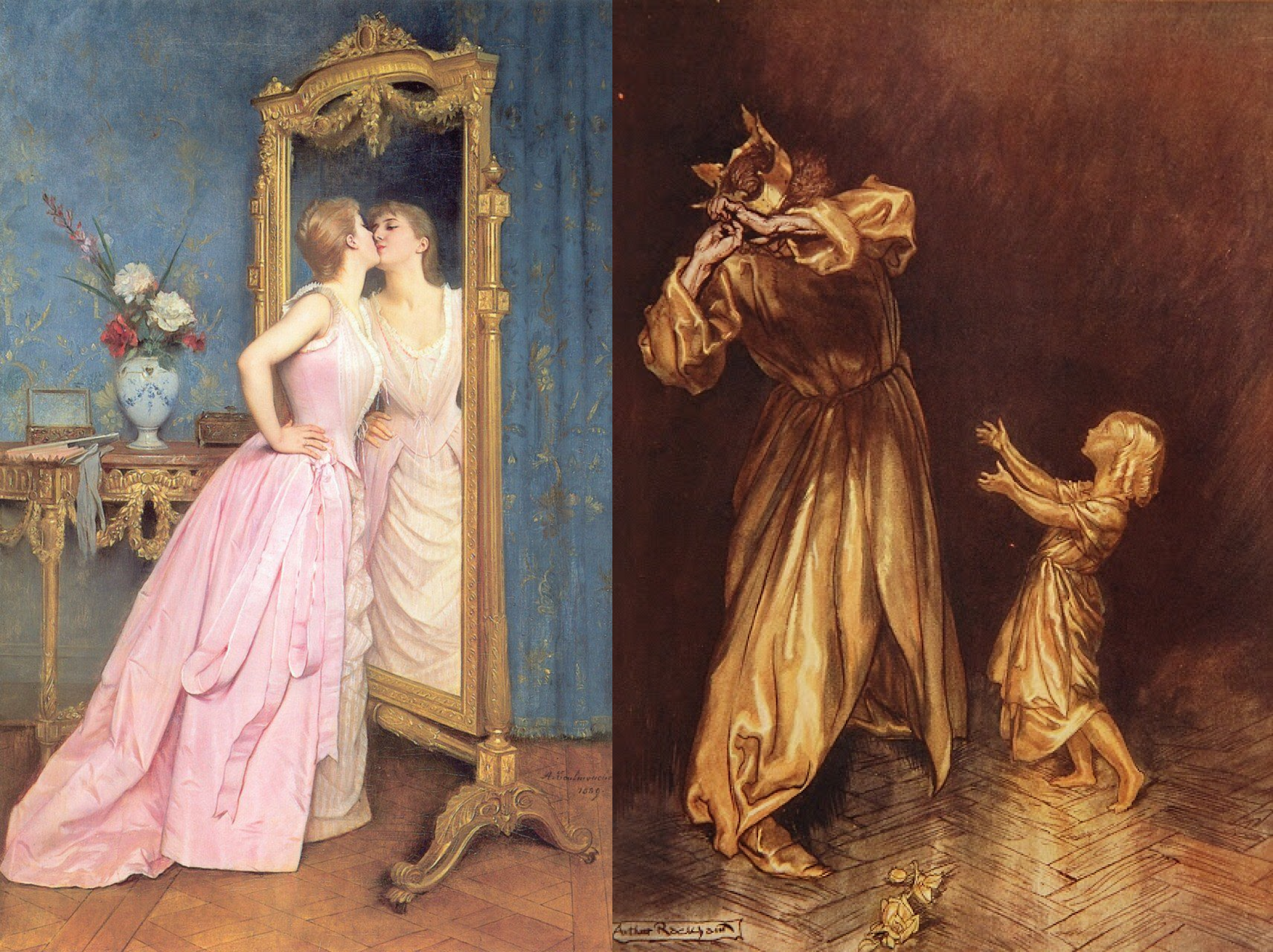

I find it strange that in an industry where risk is so central to the business, we fail to actually innovate upon and take risks within the business model itself. To me, the major “innovation” (or evolution rather) of venture has been the dogmatic bifurcation between the institutional asset managers playing an AUM accumulation game versus those who remain small and consider themselves artisans. I view all venture investors as manifesting one of two of the seven deadly sins. Everyone who takes the business seriously falls on a spectrum of pride and greed.

The greediest investors will raise large funds to maximize AUM and enjoy their risk-free 2% annual fees. For what it’s worth, this is a phenomenal business model if the goal is wealth accumulation. The proudest investors believe they’re more clever than the rest. They intentionally keep their funds small with the (mathematically correct) belief that a smaller fund can be returned more easily. Thus, the 20% makes up for a relatively meager fund size. (Shout out to Chris Paik for relaying a version of this from an unknown source on a recent Turpentine VC episode).

The “greedies” assume more risk upfront by maximizing their fundraises. Then, because the venture model breaks at scale, they are forced to accelerate capital deployment and opt for a less-idiosyncratic, beta-first strategy. The “prouds” assume less risk upfront by capping their fundraises, but push out the risk horizon as beta strategies don’t work at small scales, so they must employ tactics to discover alpha. As a result, there’s an increasing meta tension within venture and it seems that the only way to differentiate is to publicly swear allegiance to one of these camps and then make incremental improvements to the model. It’s a two-party system and you have to pick one if you want to play the game, whether you agree with all of the principles or not. Sounds familiar, huh?

At risk of overstepping my domain expertise (which I guess is the most VC thing I can do), I don’t find it surprising that this election cycle was marked by the reach of influencers and crowdsourced knowledge. Despite the outcome, I believe we’re seeing a shift away from the dominant media outlets and narratives and towards more organic conversations and factual goal-seeking. While a long-shot, I hope that this addition of variance and nuance to the process may ultimately lead to new belief systems and eventually new choices for voters.

As an American disgruntled with the lead-up and outcome to an election in which I felt like I had no surefire choice, I want more options. And in venture, I want more options too. The only way to make that happen is to take risks within the asset class itself – to try new things that break free from the two-party system led by the prouds and greedies. It’s time for us as venture investors to take on meta-risk beyond just the portfolio level and roll it into the firm level by trying new things. We must conceive of creative winning strategies, design products that benefit founders, and build trust with LPs to give them a go. We need new parties to vote for with our capital!

One strategy we’ve seen implemented is the idea around technology as an asset class on its own. Crossover investors have cut across different asset classes to capitalize on broad technological trends. We’ve seen a barbel approach become more consensus where early-stage investments are used to generate alpha for publics across shorter time horizons. LPs get a smoothing of liquidity and investors (theoretically) can recycle shorter-term capital gains back into various strategies. This makes intuitive sense and we’ve seen this approach really take off at crypto firms which have dedicated privates and liquid token strategies.

I think what we’re lacking though is more financial engineering and innovation. There’s so much talk in our industry about eschewing competition and building monopolies, but we operate in an insanely competitive and commoditized domain. We need new assets that offer a differentiated return profile to LPs while continuing to support founders above all else. We’ve historically seen the most financial innovation from mega-fund asset managers with private credit becoming the newest phenomenon. I don’t think this next product will necessarily manifest itself as a form of venture as we know it today – and it certainly won’t come from KKR or Blackstone. I am confident that a venture firm will lead the charge in experimenting with new strategies and financial products. It’s time to take on some meta-risk. It’s time to get rid of venture’s two-party system.