Shifting the Overton Window of Biohacking

Last month, @farbood took to Twitter to document receiving follistatin gene therapy, making him one of only ~200 people worldwide to get it. The most notable recipient has been Bryan Johnson. Follistatin inhibits the myostatin pathway, which regulates muscle growth. The therapy aims to promote muscle development, reduce body fat, and improve metabolic health and epigenetic age by using viral vectors to deliver the follistatin gene to muscular tissues, instructing cells to produce more follistatin.

Farbood’s results were rapid. Within 28 days, his body fat dropped 15%, he lost 10 pounds, and his energy levels and libido increased, with minimal side effects. With each update, Farbood appears evermore satisfied with his decision. To observers, follistatin seems like a miracle drug. However, the therapy lacks FDA approval and is thus not available in the United States.

The company administering the therapy is Minicircle. Minicircle conducts trials to gather human data, navigate regulatory hurdles, and bring follistatin therapies to clinics worldwide. This initial trial phase takes place in Próspera, a regulation-light Zone for Employment and Economic Development (ZEDE) in Honduras, allowing visitors to consent to experimental therapies. Próspera aims to be a medical tourism hub for those willing to take the risk. MIT Technology Review published an insightful piece on Minicircle and Próspera in 2023.

In its present form, follistatin gene therapy is reserved for a small group operating on the fringes, willing to travel to Central America to escape the well-intentioned red tape of the FDA. However, I believe broader societal interest in biohacking is beginning, and follistatin will be one of many designer gene therapies generally available to patients in the next decade. We are seeing the Overton window shift towards designer biohacking.

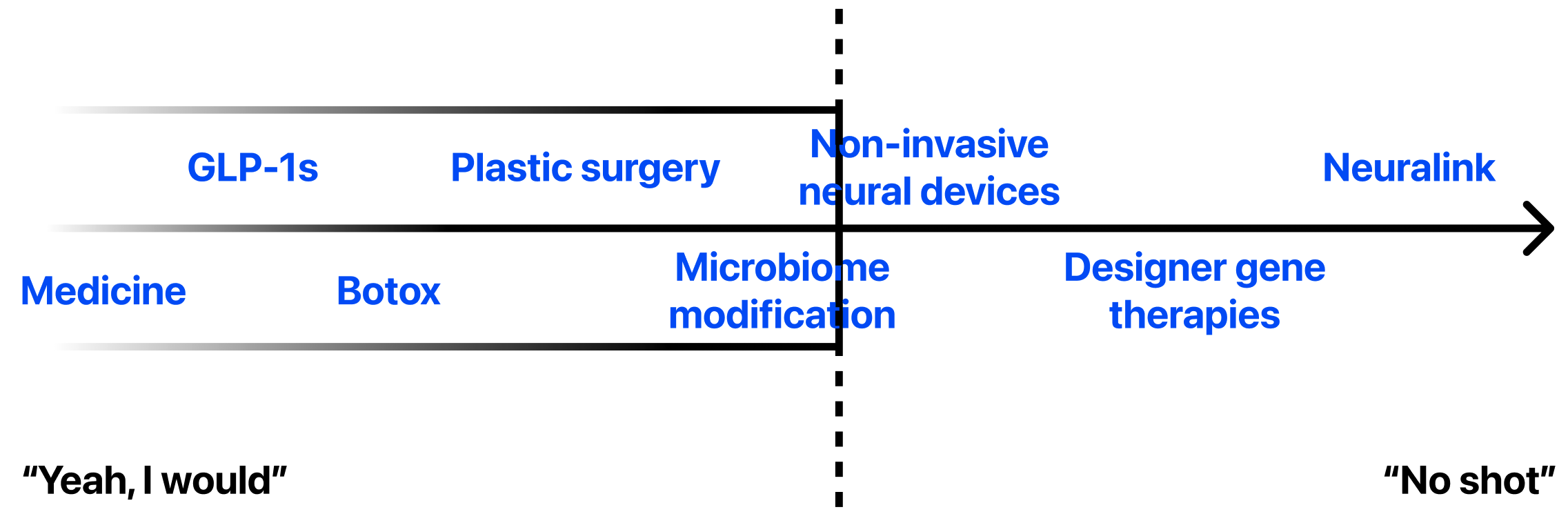

I consider biohacking to be any self-directed bodily intervention aimed at self-enhancement — from routine activities to invasive procedures. My definition and perspective of what constitutes biohacking is probably a bit broader than most, which is why I broke down a (non-exhaustive) spectrum below:

In the consensus camp, we have medicine. Any medication modifies our bodies — so yes, according to my definition this would be a very light form of biohacking. There is a separate nuanced window within this. For example, taking a Tylenol to relieve a headache would be more acceptable than oxycodone, but taking a pill to improve well-being is ordinary.

GLP-1 agonists are the new class of weight loss drugs that have sent pharmaceutical stocks like Novo Nordisk soaring. Within less than a year, we’ve seen GLP-1s transition from complete obscurity to blockbuster drugs of the decade. Still, however, there is some residual social hesitation. People often respond with “why don’t you just diet or exercise” when a friend discloses they’ve started taking Wegovy, yet without fail, they eventually accept their choice and move on. There’s a perception that weight loss drugs offer a shortcut to a healthier lifestyle, and while that’s true, technological advancements often lead to better outcomes, and this is no different. GLP-1s are here to stay and general stigma has almost all but decayed - even Equinox is offering a high-end protocol around them now.

Moving outwards, we reach beauty procedures like Botox or rhinoplasty. Society accepts these, and they sometimes even project elevated status, regardless of one’s attraction to the modification. There are even trends towards certain aesthetics, and plastic surgeons closely track the influence of celebrities and social media. Those with cosmetic work signal wealth and vanity (although a botched surgery may suggest the opposite), traits many aspire to. Again, variations exist here, but overall, we broadly accept appearance enhancement.

At this point, we reach the Overton edge, where consensus becomes unconventional. At the divide, I’ve included microbiome modification — oral or topical treatments using engineered bacteria on our skin and guts. The gut-brain axis and probiotics dominated venture discourse for some time, but replacing microorganisms with engineered versions is beginning to be explored and push towards mass consumer availability. Companies like Taxa design personal care products to rebalance the skin microbiome. Unlocked creates probiotics to improve gastrointestinal well-being. While hesitation towards manipulating bodily organisms exists, strong marketing and a focus on brand building could mitigate concerns. I consider microbiome modification the most hands-off version of fringe biohacking — introducing engineered microbes to enhance bodily functions. A mental disconnect exists between “changing my body” and “changing what lives on my body,” despite our dependence on bacteria.

Another step and we reach non-invasive neural devices impacting brain function without surgery. Stimulating our brain, by using wearable hardware like Prophetic for dreaming, offers unique consciousness alteration without the pause caused by permanence. I believe the brain represents a boundary — altering the physical self is acceptable, but tampering with the mind requires higher conviction. It progresses shedding our mortal coils and evolving beyond Homo sapiens. A wearable is temporary, but implants like Neuralink are permanent, further outside the window and towards the edge of what many would consider consensus. Neuralink began human trials of its brain computer interface, with the first implant proving successful. Patients can join future trial registries, but broad availability is years away.

Reversibility allows for second chances. The ability to change one’s mind (altered or not) is what I believe represents the largest step in biohacking acceptance and most experimental therapies in general. RNA-editing therapies are gaining traction due to the safety and flexibility they offer. Whereby other gene therapies use DNA, leading to permanent alterations of a recipient’s genetic makeup, RNA therapies only temporarily instruct our cells to produce desired proteins. I argue that transience is worth a premium in the social perception of biohacking.

This brings us to designer gene therapies. Minicircle claims follistatin is reversible thanks to the novel use of plasmids which do not integrate directly into the genome or alter a patient’s original chromosomes. However, to subject oneself to the risk of genetic manipulation for vanity’s sake is still an unnecessary risk. Life-saving therapies are often used only in dire circumstances, though they are becoming more common. The FDA recently approved Casgevy for sickle cell anemia, the first ever genome editing treatment approved. Meanwhile, the 2018 Right to Try Act allows patients with life-threatening ailments to access investigational options.

As the technology improves and regulatory bodies approve other therapeutics across other indications, then we will begin to also see designer gene therapies creep into the scope of the biohacking Overton window. It will take time, but normalization begins with products taking the form of critical therapeutics and medical devices. For example, Neuralink itself is beginning with trials targeting patients with paralysis and other debilitating conditions. Companies will require a clinical wedge to validate technology and relieve consumers of the upfront stigma that comes with biohacking. For now, we exist working towards a future where biohacking becomes the norm. If that means better drugs for the people that need it most, then so be it.